Excerpt

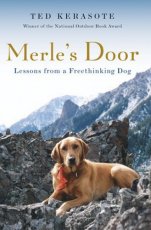

from Merle's Door: Lessons from a Freethinking Dog

Excerpt

from Merle's Door: Lessons from a Freethinking Dog

by Ted Kerasote

Lessons From a Freethinking Dog

When I met my dog Merle on the banks of the San Juan River, I was carrying a raft of notions about training dogs. It was a large—as large as the one I was about to row through those wild canyons, and most of its baggage was divided into two airtight duffels. The first was labeled “Humans Take Care Of Dogs,” and the second was called “Dogs Need The Structure Of A Pack.”

Merle disabused me of these notions from the start. There he was, appearing suddenly out of the night: a big reddish-gold dog, collarless and young. He seemed to be a yellow Lab with some other fox-colored breed thrown in. Rhodesian Ridgeback? Redbone Coonhound? I couldn’t tell. Whatever he was, he had a collected air about him. He didn’t lick; he didn’t jump; he met my eye with an expression that said, “You need a dog, and I’m it.” How did he know that I’d been looking for a dog for over a year? He did, just as he knew so many other things.

He knew how to avoid rattle snakes; he could catch ground squirrels with stunning consistency; and he could run down a calf neat as a wolf runs down a deer (a habit we soon got rid of). Fit and rangy, he had been surviving on his own in the wild. In fact, his morphing between the habits of a wild dog and those of a domestic one took us on a journey in which he, the dog, became a bit more civilized and I, the man, became a tad more wild. Along the way, my raft of dog-training notions capsized, not once, but many times. Some of its baggage I salvaged because it was, and is, useful, and some was swept away forever.

The first of my notions to go was that humans, as dogs’ caretakers, need to provide them with toys. After Merle and I returned to Wyoming, I, thinking that he needed some entertainment in his new home, bought him rubber bones, balls, and rawhide chews. He displayed zero interest in them. What he wanted to do was exactly what he’d been doing when we’d met in the desert—explore the world with his nose.

That he would be more interested in the outdoors than with toys should have been obvious to me, but it wasn’t. No surprise. Humans are visual creatures and, these days, most of us learn about the world through books, TV, and the Internet. Dogs, by contrast, still learn about the world experientially, through their noses and paws, and no artificial toy can replace the authentic odors of the outdoor world and its constantly changing stimulation. To facilitate Merle’s desire to stay in that world, I gave him his own dog door so he could come and go as he wished.

The door soon helped to sweep away another piece of my self-centered baggage—in short, that my company was enough for my dog. When Merle left the house, for whom did he make a beeline or rather a dogline? Of course, the village’s other dogs, his behavior revealing another truth about the canine world: Dogs often find their own kind more entertaining than they find us. Not only do they learn a whole new world of smells from other dogs, they also observe them doing canine things; they accumulate knowledge that’s impossible to assimilate from bipedal, sight-oriented humans. Such canid-specific learning keeps dogs mentally sharp, just as books, TV, and the Internet help to keep us well informed.

Today, such paws-on freedom to learn is limited for most dogs because of where they live—cities and suburbs. Nonetheless, town dogs still have a chance to get a good canine education. Many city parks have dog-friendly hours during which dogs can run off-leash, savoring the joyous scent of other free-running dogs and the smells of the outdoors. Numerous studies have shown that it’s these dogs—enjoying daily off-leash time—who are better socialized and calmer than those dogs who spend their entire lives in a fenced yard or on a lead.

The third of my dog training notions that disappeared after living with Merle was that dogs need and are also happier within the structure of a pack, their human acting as an alpha wolf who tells the subordinate members of the pack how to behave. However, I soon realized that Merle learned best when my authority was least. He watched, he listened, he imitated. He did some things in the way I asked him to do them, for instance sleeping only on the dedicated quadruped couch; others he did in the way he wished, particularly eating at a time he had chosen.

This sort of flexibility between packmates—free will with some rules—is the way wolf families are actually structured. The prevailing notion that wolves live in rigidly hierarchical packs has come from watching captive wolves, who have been forced to live in unnatural settings and behave dysfunctionally. When researchers have observed wild wolf packs during the last decade, they’ve discovered that an alpha male and female share leadership, and then delegate some of that leadership to their maturing pups, who are given the chance to make decisions about whom to hunt, when to hunt, and where to move the pack.

These findings have enormous implications for how we live with our dogs, who are genetically and psychologically wolves. If we thwart a dog’s natural maturation from youngster to responsible adult by micro-managing its behavior, we arrest it in childhood. Such perpetual puppies often act out, just as human children do if they’re overly constrained.

This isn’t to say that dogs should be allowed to do anything they want: bark at passersby, jump on them, or tow their human around at the end of a leash. Hardly. Just as wolf pups learn the etiquette of the wild, so, too, must dogs learn the manners of civilization. This still leaves ample room, however, for a dog to be a dog. And for most dogs a big part of being a dog means the chance to fulfill their curiosity by exploring on their own.

Individual wild wolves act this way all the time. The wolf will scour the countryside and return to its pack, telling everyone, “Guess what I found! Come look!” Merle acted in the very same way. After a long solitary recon, he’d come bounding up to me, his paws dancing, his eyes full of excitement, as he exclaimed, “Come quick! Let me show you what I smelled!” When I followed him, I’d often find the sign of elk, wolf or grizzly, sometimes the animals themselves. We were partners, not perfectly equal ones, but ones who recognized each other’s expertise. In the wild, I deferred to him; in streets crowded with traffic, he deferred to me. I wasn’t his alpha; we were an alpha pair.

It’s true that our relationship was fostered by the wild country surrounding our home. Yet its major attribute—a human’s respect for a dog’s full personality—can be nurtured anywhere. It’s not a question of geography, but of attitude. This, too, was one of Merle’s lessons: The more often a human can replace a dog’s physical leash with one of trust, the happier the dog will be.