Excerpt

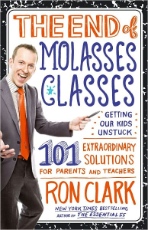

from The End of Molasses Classes: Getting Our Kids Unstuck--101 Extraordinary Solutions for Parents and Teachers

Excerpt

from The End of Molasses Classes: Getting Our Kids Unstuck--101 Extraordinary Solutions for Parents and Teachers

by Ron Clark

Not Every Child Deserves a Cookie

Last year one of our new fifth graders was really struggling.

He entered RCA below grade level in every subject and he was

failing several courses. When I met with his mom she defended

her son by saying, "Well, he made all A's at his other school."

When I told her that was shocking, she explained that he had

done so well because he had a really great teacher. Urgh!

There is a misconception in our country that teachers whose

students make good grades are providing them with a good

education. Parents, administrators, and the general communiry

shouldn't assume good grades equal high academic mastery. In

fact, in many cases those teachers could be giving good grades

to avoid conflict with the parents and administration. It's

easier to fly under the radar and give high grades than to give

a student what he or she truly deserves and face the scrutiny of

the administtation and the wrath of an angry parent.

I have attended numerous awards ceremonies where practically

every child in the class received an honor roll certificate.

Parents always cheer, take pictures, and look so proud. I just

sit there and think, Ignorance is bliss. Are these kids

really being challenged, or are they only achieving mediocre

standards set forth by a mediocre teacher in an educational

system that is struggling to challenge even our average

students? Yet, all of the parents look so proud and

content.

The worst part about it, however, is that I am afraid most

parents would rather their child get a good education where they

received straight A's and praise than an outstanding

education where they struggled and received C's.

At the beginning of every year, I give my fifth graders an

assignment. They have to read a book and present a project on

one of its characters -- specifically, they have to figure out a

way to cleverly show such details as what the individual kept in

his heart (what he loved the most), saw with his eyes (his view

of the world), "stood for" with his feet, and held to strongly

in his backbone (his convictions). I encourage the students to

"bring it" and to use creativity and innovation to bring the

body of the character to life.

Most of the students will bring a trifold where they have

drawn a body and labeled the locations. Some will use glitter,

and some will be quite colorful. I am sure in most classrooms

the projects would receive high grades, mostly A's and B's. I,

however, hand out grades of 14, 20, 42, and other failing marks.

The parents and students are always upset, and many want an

explanation.

I ask them to trust me, and I explain that if I gave those

projects A's and B's, then the students wouldn't see a reason to

improve their efforts on their next assignment. Some staff

members have even said, "Ron, but you know what that child is

dealing with in her home, and you know she did that project all

by herself." I quickly tell them that society isn't going to

make excuses for their home situations, and we can't either. If

we make excuses and allowances, it will send the child the

message that it's okay to make excuses for his or her

performance based on circumstances, too. We just can't do it. We

must hold every child accountable for high standards and do all

we can to push the child to that level.

I recall giving one fifth-grade student a failing grade on her

first project. She cried and cried. She had never made less than

an A on her report card, and her mother was devastated, too. I

explained that the low grade would be a valuable life lesson,

and I gave the young girl, and the rest of the class, tips and

strategies for receiving a higher score in the future. I showed

them an example of a project that would have scored 70, a

project in the 80s, and a project that would have earned an A.

I was pleased to see that her next project came to life with

New York City skyscrapers that were sculpted from clay,

miniature billboards that contained academic content, and

streetlights that actually worked. The project was much, much

better, and it received a 70.

As a final project, the students were instructed to create a

time line that would contain a minimum of fifty significant

dates in the history of a specific area of the world. The same

young lady brought in her final assignment wrapped in trash

bags. Removing it, I saw a huge, four-foot pyramid, a replica of

the Great Pyramid of Giza. The student had made it out of

cardboard and apparently had used sandpaper to make it feel like

a real pyramid. It was beautiful, but it didn't contain a time

line, so I told her the grade would not be passing.

She grinned at me, walked over to the pyramid, touched the top

point, and suddenly three sides slowly fell open, revealing the

inside. She had carved her outline on the inside, using detailed

pictures, graphs, and descriptions of 150 major events. She even

had hand-carved Egyptian artifacts and placed them throughout

the inside of the pyramid, just as you would find in the tomb of

a great pharaoh. She had handmade mummies that she had learned

how to make on the Internet. She looked at me and said, "Mr.

Clark, I have worked on this for weeks. I wanted it to be good

enough. I wanted it to be an A." It was miraculous and

spectacular. I looked at her, full of pride, and said with a

smile, "Darling, it's an A."

If her initial project hadn't been an F, she never would have

walked in with that pyramid. That child is about to graduate

RCA, and she is ready to compete with any high school student

across the country. She knows what high expectations are, she

understands the value of a strong work ethic, and she knows how

to achieve excellence. If we continue to dumb down education and

to give students A's and B's because they "tried," we are doing

them a disservice and failing to prepare them to be successful

in the real world. That young lady couldn't walk into an elite

high school and compete with a glitter-filled trifold. However,

she can walk into any high school with that pyramid and her

overall knowledge of how to achieve that type of excellence and

stand high above her peers.

I often bake cookies for my students. I tell them it is my

great-greatgrandma's recipe and that she handed it to me in

secret on her deathbed. (Okay, a stretch.) As I pass out the

cookies, the kids who are working hard receive one with delight;

the students who aren't working as hard do not. Parents will

call and say, "Mr. Clark, I heard you gave every child in the

class a cookie except my child. Why are you picking on my

child?"

Why does every child have to get the cookie? The parents claim

that I will hurt the child's self-esteem. Has it really gotten

to the point that we are so concerned with our children's

self-esteem that we aren't realistic with them about their

performance and abilities? If we give "cookies" when they aren't

deserved, then we are telling our young people that they don't

need to work hard to receive rewards. We are sending a message

that the cookie will always come. That is why we have so many

young people in their twenties who have no idea what it means to

work hard. And that is why they are still looking to their

parents to provide support (and to give them the cookie).

I tell my students who don't receive a cookie that I will be

baking cookies the following week. I tell them that I will watch

them until that time and that if they are trying hard they'll

earn their cookie. It is shocking to see how much effort kids,

regardless of their age, will display to get a cookie. And when

it is earned, it means something. The students will glow with

pride, and they will explain how they are going to eat half the

cookie then and save the other half for later. Also, it tastes

better than any cookie they have ever eaten, and it sends the

message that with hard work comes rewards. If parents and

teachers are just rewarding our kids without cause, we aren't

teaching the value of personal effort.

We all need to teach our young people that not everyone

deserves a pat on the back just because we are attempting to

make everyone feel good. Giving praise that isn't earned only

sets up our students for more failure in the long run.

If you are a teacher who wants to increase expectations but is

afraid of the backlash from giving failing grades on assignments

that will cause your parents and administration to freak out,

there are some steps you can take to protect yourself When you

give an assignment, show your students beforehand what you

expect. Show a detailed description of what would earn a failing

grade, a passing grade, and an outstanding grade. Share that

with your administration as well to make sure it meets their

approval, and then make your parents understand the

expectations. Letting everyone know what is expected beforehand

will leave no opportuniry for complaints after the grades have

been given.

If you are going to give rewards, such as cookies, let the

parents know the classroom behaviors that will earn the reward

and the behaviors that will not. When students are struggling,

let the parents know specifically the areas that need to be

addressed. If the child still does not meet the criteria, you

have been clear about your expectations and therefore negative

conflicts can be avoided.

The above is an excerpt from the book The End of Molasses Classes: Getting Our Kids Unstuck -- 101 Extraordinary Solutions for Parents and Teachers by Ron Clark. The above excerpt is a digitally scanned reproduction of text from print. Although this excerpt has been proofread, occasional errors may appear due to the scanning process. Please refer to the finished book for accuracy.

Copyright © 2011 by Ron L. Clark, Inc, author of The End of Molasses Classes: Getting Our Kids Unstuck -- 101 Extraordinary Solutions for Parents and Teachers