Excerpt

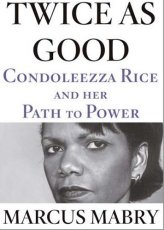

from Twice as Good: Condoleezza Rice and Her Path to Power

Excerpt

from Twice as Good: Condoleezza Rice and Her Path to Power

by Marcus Mabry

Chapter Twelve

Storms

It is one thing to have a limited political goal and to fight decisively for it; it is quite another to apply military force incrementally, hoping to find a political solution somewhere along the way. A president entering these situations must ask whether decisive force is possible and is likely to be effective and must know how and when to get out.

Condoleezza Rice

Foreign Affairs

January/February 2000

Condoleezza Rice had been working flat out since becoming secretary of state in January, delaying her vacation until the last days of August. The president had been on his vacation for weeks. In fact, Bush was on the way to setting a presidential record, surpassing Ronald Reagan for time spent away from Washington. When her holiday finally came, Rice embraced it with the same intensity she brought to her job. Escaping from work was one of the ways she maintained balance -- like her daily workouts, her sessions with her chamber music group, and her Sunday calls to friends and family.

She left Washington for her vacation in New York on Wednesday, August 31. That afternoon she hit some balls with Monica Seles, and that night she took in the sold-out Monty Python musical, Spamalot, on Broadway. On Thursday morning she indulged her shoe obsession, shopping at Ferragamo on Fifth Avenue. While Rice was out, her communications chief, Jim Wilkinson, back in his room at the Palace Hotel at Fifth and Madison, came across an item on the Drudge Report:

Eyewitness: Sec of State Condi Rice laughs it up at 'Spamalot' while Gulf Coast lays [sic] in tatters. Theatergoers in New York City's Great White Way were shocked to see the President's former National Security Adviser at the Monty Python farce last night -- as the rest of the cabinet responds to Hurricane Katrina . . .

Wilkinson's heart sank. The thirtysomething aide was so attentive to Rice's image that before she gave speeches in drab hotel conference rooms abroad, he fussed with the backdrop and podium to make sure the pictures would show what the city she was in. And it was Wilkinson who stage-managed her airport arrivals to make them look presidential. It was no secret that he hoped Rice would run for president some day. And now this. Hurricane Katrina had made landfall early Monday morning. Initially, weather forecasters thought New Orleans had dodged a bullet; when the storm hit sixty-five miles southeast of the city, it had been downgraded to a Category Three hurricane from a potentially cataclysmic Category Five. But by 8 a.m. on Monday, one of the city's central canals had been breached. The nearby Lower Ninth Ward, largely black and poor, was under six to eight feet of water, and soon eighty percent of New Orleans was flooded. Mayor Ray Nagin reported "significant" loss of life; bodies could be seen floating in the floodwater. Looting erupted.

Fifteen to twenty thousand residents took shelter in the Superdome, which was a designated "refuge of last resort." Another nearly twenty thousand crowded into the Convention Center, even though it wasn't a designated shelter and had no food or water. On Tuesday morning, Louisiana governor Kathleen Blanco ordered the evacuation of the city, but no transportation was available to move anyone. By Wednesday, when Rice left for her vacation, the media was reporting that thousands were dead in New Orleans, and television screens filled with the images of the survivors. They were almost all African American, their eyes desperate, many carrying babies and what possessions they could grab as the waters rose. Reporters who had covered the Third World compared the scenes to refugee crises they had seen.

By Thursday, the situation had gotten even worse. Every hour, the cable news channels showed a dead woman in a wheelchair outside the Convention Center, covered with a sheet, under the now clear skies of New Orleans. Despite what Drudge reported, no one seemed to be responding to Katrina.

Wilkinson -- a native of East Texas, whose family had supported civil rights before it was fashionable for whites to do so -- was concerned enough about the images of African Americans stranded, begging for water from camera crews, that he conferred with Rice's other top advisers about whether Condi needed to return to Washington. "That woman needs a vacation," said one of Rice's advisers who was also a friend. In fact, all of Rice's staff agreed: She had set travel records jetting around the globe, and she deserved her downtime. And besides, she was secretary of state, not the interior.

But within hours, they regretted the decision. The New York Post's gossip column ran a piece reporting that Rice was working on her backhand with Monica Seles. Then the gossip and news Web site Gawker posted a story headlined "Breaking: Condi Rice Spends Salary on Shoes."

. . . So the Gulf Coast has gone all Mad Max, women are being raped in the Superdome, and Rice is enjoying a brief vacation in New York. We wish we were surprised.

What does surprise us: Just moments ago at the Ferragamo on 5th Avenue, Condoleeza [sic] Rice was seen spending several thousands of dollars on some nice, new shoes (we've confirmed this, so her new heels will surely get coverage from the [Washington Post's] Robin Givhan). A fellow shopper, unable to fathom the absurdity of Rice's timing, went up to the Secretary and reportedly shouted, "How dare you shop for shoes while thousands are dying and homeless!" Never one to have her fashion choices questioned, Rice had security PHYSICALLY REMOVE the woman.

Angry Lady, whoever you are, we love you. You are a true American, and we'll go shoe shopping with you anytime.

On Friday, the New York Daily News would report that Spamalot audience members had booed Rice when the lights came up. Then, the paper would ask, "Did New Yorkers chase Condoleezza Rice back to Washington yesterday?"

Rice says that no one chased her anywhere: "On Thursday morning I got up, I had breakfast, and I went down to Ferragamo. I came back. Things had gotten pretty bad, and plus I learned that the State Department had a problem; our New Orleans Passport Center was down. And . . . the pictures were really ugly. I called the president and I said, 'I think I should come back.'"

Rice insists the alleged encounter with the angry woman at Ferragamo never happened. "Absolutely not . . . this stuff just gets out there."

And in a country outraged by the tragedy unfolding in New Orleans, the tale of the angry shopper did get out there. And -- like CNN anchor Anderson Cooper's verbal lashing of Senator Mary Landrieu for politicians' diddling while rats ate dead bodies in the streets -- shot around the Internet. Later director Spike Lee would try to find the irate Ferragamo shopper, unsuccessfully. But in Lee's searing 2006 documentary, When the Levees Broke, African American social commentator Michael Eric Dyson took Rice to task: "While people were drowning in New Orleans, she was going up and down Madison Avenue buying Ferragamo shoes. Then she went to see Spamalot!"

Dyson muddled Ferragamo's address and the chronology of Rice's holiday, but he captured the sense of anger, even betrayal, that many African Americans felt toward the administration in general and Condoleezza in particular in the days after Katrina.

The criticism took Rice by surprise. "These are not my accounts," she protested to Chip Blacker, referring to domestic issues.

"I was watching on the news what was going on with Katrina. I wasn't getting the reports of what the hurricane was going to do or anything like that," says Rice. "And so I responded like the secretary of state, which is [to] worry about the foreign contributions, worry about the [New Orleans] passport center. But it was less than twenty-four hours before I realized it was time to get back.

"Look, I'd be the first to say I learned something from that. I thought of myself as secretary of state; my responsibility is foreign policy. I didn't think about my role as a visible African American national figure. I just didn't think about it."

That Rice hadn't realized that she had a role to play as a black leader was a result of how she saw the world. John and Angelena's efforts to invest their daughter with a limitless sense of possibility, to make her unconquerable, had made her both less confined by race and less conscious of it.

By the time Rice returned to Washington on Thursday afternoon, President Bush was facing a public furor of his own, centered around the photo the White House had released of Bush peering out the window of Air Force One, surveying Katrina's damage on his way back to Washington from Crawford. Presumably, the White House intended to show a concerned commander in chief; instead Bush had looked detached and powerless.

Watching the disaster coverage in her seventh-floor office at the State Department, Rice decided she had to go home to Alabama to show that the administration cared. An aide phoned the White House to clear the trip, but the White House resisted; the president should travel to the gulf first, and he was planning to go early next week. But Rice's office was adamant: The secretary needed to be down South "with her people." They reminded the White House that they had their own planes. The White House called back three hours later; Rice had been cleared to go. The president would go earlier.

Copyright © 2007 Marcus Mabry